The rope from the neck of a hanged man

The rope from the neck of a hanged man

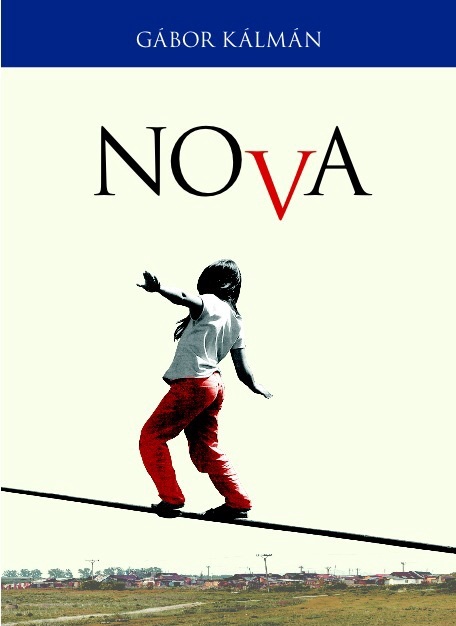

(Nova)

Translated by Robert Smyth and Ágnes Molnár

Sklenár kept it secret that he had held on to a rope taken from the neck of a hanged man, having stashed it under the bar. For decades, it lay there below the sink, under the cover of the inside shelf that was stacked with all sorts of stuff; dishwashing liquid, soda siphon cartridges and discarded empty Slatina[1] bottles, where only the pipe coming out of the sink’s siphon reached out to subsequently disappear into the mouldy brick wall.

Sklenár revealed his secret in his dying voice to his son, Vlado, before he expired in the creaking, time-worn Škoda sanitka[2] on their way to the town clinic. Vlado wasn’t exactly happy that his dad, instead of simply dying, was making a scene. Vlado wished to get over the whole thing as soon as possible, so he nodded approvingly, whereby he didn’t actually mean to imply that he understood but was instead rather keen to hurry the old man up, to let him say what he wanted, so that they could then both go their separate ways.

Up until this point in time, Sklenár somehow thought he could get away with it, because in Jasná Horka everybody had a bizarre story, and most people inherited one anyway, one that they came into with their family name. No wonder people in neighbouring villages were afraid of them. All Jasná Horka citizens are a bit deranged, they would say.

The ramshackle Škoda sanitka that reeked of faux leather almost fell apart on the way, the decrepit car-body shook and rattled. Rust had damaged it, the upholstery was torn, the door of the glove-compartment was broken, and large chunks were missing from the inside locks’ plastic fasteners. The cream-coloured cover had worn off from the windows of the cargo hold that had been turned into the patient compartment. It was an old, front-engine Škoda 1203 minibus, although the Škoda elf-head emblem was missing from the front, just like the disks from the wheels, although they might have been missing even when it came off the production line. This made Vlado contemplate that he had never seen disks on the wheels of any Škoda sanitka, even though this model was quite popular, ever since they started using them for the ambulance service, which might have been 15 or 20 years ago. Vlado tried to recall the first time he saw a Škoda 1203. A hot summer day sprang to mind when, still as a child, he saw a brand new model, a shiny red one. It was whizzing alongside the corn fields, and he ran after it barefoot as far as he could, because he had never seen such a beauty – such a foreign and exciting object – before in Jasná Horka.

Vlado was familiar with the old superstitions and his father’s confession did not surprise him in the slightest, but old Sklenár was on his last legs. He strongly squeezed Vlado’s hand and crankily told him how he got hold of the rope, the face the blonde Nemec[3] had pulled as he was swinging with his head turning blue, and how the Nemec must have surely regretted it by then, for that’s how Sklenár described it.

Vlado silently removed his hand from his father’s grip and pulled himself backwards. Later, he didn’t really understand his own reaction. Vlado wasn’t especially moved by the incident. It happened as it happened; it was no big deal, worst deeds had been committed and the world didn’t stop turning. But at the time, in his embarrassment, he stared at the Škoda santika’s rust-devoured floor, then contemplated a spot on his botaskys[4] where the thread had come unravelled and a piece of faux leather was hanging loose. He even contemplated that these botaskys cannot be worn for longer than a single summer because if the thread the faux leather pieces are stitched together with unravels, then you might as well just throw them away as they are, because then the thread comes out of the seam within a few days and there is a hole in the trainer. By the time Vlado came to his senses, old Sklenár was quiet with his head tilted to one side. The Škoda santika had become silent. The siren – which had wailed pointlessly even until then only because the driver enjoyed using it – had been switched off. Coughing and rattling, they drove along the vacant roads, which had been built in a hurry and had quickly become dilapidated, despite hardly any cars using them.

Vlado dug out the rope from under the bar on the very same day. Covered in thick grey dust, it was also sticky from beer froth and wine stains, with fist-sized dust mites and bits of mould stuck to it. Scattered small coins rolled out with the rope – worthless, rusted tin disks. Vlado didn’t feel like touching the rope, so he plucked at it with a piece of wood and eventually touched it with a newspaper. He held it well away from his body and took it to the bin, grimacing disgustedly throughout. The newspaper opened out as it fell and covered the blackened rope that landed on the top of the litter pile. On the cover of that day’s paper, the crew of the star-ornamented tanks were waving farewell, with star-ornamented ammunition ušánkas[5] on their heads, and with gentle, lenient smiles on their faces, of the type one can only see on the faces of armed men when they’re facing the unarmed.

Vlado, who people started calling Sklenár almost immediately in the wake of his father’s demise, felt the weight of the moment, and looked at the departing tanks on the grey newspaper photo and the mouldy piece of rope that was sticking out from underneath it. That’s how the world changes, he murmured to himself, and for a few seconds, he directed his gaze over the hills rising above Jasná Horka, but then he suddenly realized that he was standing over a dingy bin. He shook himself and never thought of it again. That was until at the end of the following month, when he took stock, and the 20 per cent loss to the bar’s takings materialised. He shuddered as cold sweat poured down his back, but he reassured himself that it was only an old, silly superstition, and the only reason for the setback of the business was the late summer when less wine is sold.

The Sklenárs were famously superstitious. Vlado’s grandmother, Boženka Sklenárová, who had been mourning Vlado’s grandfather since the war, knew all the superstitions and beliefs. In fact, older people used to meet up with her to discuss good and bad omens. Widow Sklenárová didn’t live far from the cemetery on the Cintorínska[6]. When she died, she literally only had to be carried next door. She hardly left a thing after herself and only just enough money for her funeral. There wasn’t much work with her. For Sklenárová’s special request, she was buried there, even though the upper cemetery had not been in use for several decades. This was due to the scary, skull-shaped wood carvings on the cemetery gate which were the work of an outsider who happened to be in the village only the once. Sklenárová’s windows overlooked the unattended wooden crosses with plaster, sky-gazing Mary reliefs on them and also the tower of the cemetery’s church that stood lonely on its own.

Her house was a sturdy mountain hut made out of timber and ornamented by neat wood carvings that had faded to pale brown with the passage of time. A tall gate locked out the outside world, not leaving any glimpse into the garden, just like all the other houses in Jasná Horka. The two porthole-sized windows hardly let any light into the house. She had two rooms, out of which she never used one and the other only in the winter, as she otherwise spent her time next to the iron stove in the summer kitchen that was filled with sweetcorn and a sickening smell of fat all year around. She wasn’t on good terms with her neighbour, Štrofekova, who rejected all superstitions and old beliefs. Štrofekova didn’t believe in God either, only in rules and perhaps the cooperative, but even that she could have made better if she had been asked to do so. On the other hand, Sklenárova thought Štrofekova was a witch, so whenever she could, she tried to avoid her neighbour.

It was the cause of great concern for Štrofekova that her own mother, grandmother, great-grandmother and great-great grandmother, and even she herself, had been widowed within a year or two of getting married, and they mourned their husbands in raven coloured clothes until the end of their lives. The whole family looked like a tableau straight out of a horror story. So Sklenárova didn’t go out of her garden too much. She was busy with her twig brooms all day and there were piles of them next to her house. She worked with the best privet branches and she used cans, the medium-sized, luncheon-meat ones, often without even soaking the paper off them, for tightening up the twigs. Hearsay had it that Sklenárova invented the method herself, and everybody else learnt it from her.

So Sklenárova knew of all the old beliefs and she understood everything, even when she had to fish out the female member of the village’s sole gypsy couple – the wife of ‘uncle’ Tomaš, ‘aunty’ Tomaš – from the toilet. Incidentally, she was given a male name due to the pre-war financial provision whereby if newborns were given the same name as the prime minister, the family would receive 300 Koruna, which is why the country was full of people called Tomas.

It was only the question of a split second that Sklenárova didn’t actually end up shitting right onto aunty Tomaš’ head, in the early dawn when she was about to drop her morning defecation. Sklenárova was still sleepy and numb, and her hearing also served her less reliably in her old age. She was already sitting on the constantly damp wooden toilet seat, since just as in all the other gardens in the village, the men used the loo for urinating as the garden was not meant for that. Although Sklenárova was a widow, she’d had her fair share of wet wood due to her son and grandson. She was already sitting with her groin perched over the hole in the bittersweet-smelling shack, with the scarce dawn light coming through the small carved gap, when from the depth of the latrine she heard the whining of aunty Tomaš.

What made things even worse is that the gypsy couple were not called whiners for nothing – for they couldn’t even utter a single comprehensible sound. They spoke indiscriminately, whining and burbling as if they were half animal. According to many people, it was because they’d drunk their brains away. Other people in Jasná Horka also drank but nobody had ever seen anything else at the home of uncle and aunty Tomaš than Nova[7] wine. They even grew the grapes by themselves. What’s more, evil wagging tongues had said for ages that Nova wine is poisonous, that it eats away the people so that at the end they shit their guts out, but before that they go mad. Of course, others said that there wasn’t a better grape as it withstands everything that nature can throw at it and that Nova is life itself.

They washed off aunty Tomaš but the stench around her was still unbearable as she stood wretchedly, shit-stained up to her waist. The two Sklenárs, Boženka’s son and grandson, who had appeared on the scene in the meantime, held their noses as if it wasn’t the shit of their own family. Sklenár felt sorry for aunty Tomaš, and threateningly waved at his son who roared with laughter. He gave a bottle of fruit brandy to aunty Tomaš, so that she could calm uncle Tomaš down with it and block out the mockery. At that time, it must have been at least a hundred years since someone had tried to calm down their shocked husband with some other women’s shit.

The Sklenárs didn’t do well during the war. Nobody did of course, but the Sklenárs did especially badly because the men from the village carried out partisan attacks in the hills or were deported, and women didn’t really go to the pub. The Sklenárs offered cheap, good quality wine and a lot of people from neighbouring villages bought wine from them as they also sold other wines than Nova. When every now and then, the Red Army or the Nemec appeared, they were given drinks for free. More exactly, in return for the free wine, they decided not shoot old Sklenár in the head. So there was a payment for the wine, which was life itself, but what was it good for when there was no money to live off, as Sklenár used to say, and he hated the whole thing together with the Red Army, the Nemec and the partisans who chased each other out of the Jasná Horka hills at least three times within a year.

Back then, a group of men in uniform suddenly appeared and they got blind drunk on the Sklenárs’ wine and slapped around a few villagers who had not enlisted because of their age. Then they were not seen for some time, but the bangs and the explosions became louder in the hills, and people who happened to go through the forest saw more and more dead bodies in the snow among the trees. Finally, one morning following a night that was filled with really loud sounds of battle, a completely different group arrived. They wore different uniforms and spoke a different language. The group usually drank themselves silly on the Sklenárs’ wine and hit some villagers who were not enrolled because of their age. When they were feeling really lazy, they didn’t tire themselves out by trying to find someone to strike, but rather beat up Sklenár instead. The bartender rigorously counted the barrels and the bottles, the expected yield, trying to predict how long the war would last. They would survive as long as there was wine.

“Oh, Boženka,” he used to say in a weepy voice to Sklenárova who was unbecomingly young compared to himself after such assessments. “This madness can only last another year and a half. Maybe we can hold on until then,” he moaned. He studiously added everything up.

Sklenár still had five large ászok barrels – two full of Nova, two of Muscat and one of Frankovka. He counted the daily consumption, including that of the invading Reds and the Nemec, the free boozing and what they drank themselves. There wasn’t a better counter around than him. Sklenár didn’t use paper in the pub either, but he kept the daily volume in his head. He knew it to the decilitre, to every crown, including advance and back payments, invitations and returns, the total inventory was in his head to the nearest halier[8] at the time he shouted closing-time.

He must have lost around 150 hectolitres, which was his complete fortune apart from the five barrels he kept in the small cellar under his house when the press house above Žabia Hora was hit. Soldiers wanted to break into the cellar under the press house and in their drunken stupor they drove a tank into the arched entrance of the cellar that was dug into the steep hill, but the hard quarry stone wouldn’t give way, with the rock pieces squeezed into the arch further fortifying it. So, they simply shot the cellar door down.

Behind the cellar door, 10 ászok barrels stood – eight Nova and two Muscat – each one of them of at least 15 hectolitres, and there was also some Borovička. But old Sklenár only felt sorry for the old ászok barrels. The tank blew them all up. In the tunnel-like cellar underneath the press house, the oak staves of the barrels snapped and burst, the hoops sprang and let go with a shriek. They gave out a sound like the suppressed bark of a smaller Kuvasz dog, then with an ear-splitting noise, 150 hectolitres of wine sprayed out, making foam through the oak debris around. After the explosions, the waves of wine oozed out, pushing what was left of the iron oak staves.

The hillside was spewing out a jet of wine. The drunken soldiers appeared, sliding down on their backsides, swept along in the stream of wine until the edge of the rock from where the stony and rocky hillside dropped off even more steeply until it reached Žabia Hora. This would have been the smaller problem but the tank also perched awkwardly on the hillside. They’d already been drunk when they drove it there. Half of the tank’s caterpillar tracks hung in the air, the other tracks snagged on the hill at the cellar’s arched entrance. On the other side, the metal tracks clung to the loose, dusty soil, which the mounting flood rapidly washed away. The monstrous war machine tilted, the soft ground subsided underneath it and there was no way of stopping it. It was enough for it to slip a couple of metres down to the side of the grape rows, the flow quickly pulled it from the edge of the rocks and the tank, rattling and cracking, slid down as far as Žabia hora, at the bottom of the hill. In the meantime, the Nova sparkled around it in the beaming sunshine, the wine stream formed foaming ridges everywhere, poured into a ditch in the side of the hill, then sprawled out onto the dirt road at the Žabia Hora crossing like a huge spit with light, sleazy foam stains on the surface. The locals called the case the ‘Revenge of Sklenár’, but every rose has its thorn and the drunken soldiers bombed the hillside in their anger. They fired until there wasn’t anything left to aim at, until the thin soil was scattered by the blast and the press houses and cellars collapsed one after the other.

Sklenár could thus only count on the wine that he kept in the cellar under his pub and what he could produce – in a borrowed cellar – from the meagre crop of grapes that survived. So the available amount of wine was significantly loss-making. No wonder Sklenár was pleading diligently to all sorts of gods and mother earth, in fact to whoever popped into his mind, so that the war should end in a year or two. It happened that way but this Sklenár didn’t live to see it, his heart took him.

The younger Sklenár was still out on the hill. More bombs were dropping than ever before, the soldiers chased each other among the trees. Sklenár was also running up and down and prayed as hard as he could to survive. Nothing else mattered to him too much. When he saw the soldiers running to the right, he did the same, when they charged, he acted as if he was charging too. Of course, he also saw that everybody was putting on a show around him, every attack was a sham and it was an act on the other side as well. The small Sklenár might have even enjoyed it, if at times some truly real bullets didn’t fly past his head. He thought they might as well sit down for a fruit brandy and a game of cards, no one had any strength left for anything else, as they were all dead tired. Sklenár was too, he only managed to raise his gun to his shoulder very slowly and it took him ages to shoot it randomly once or twice.

He wouldn’t even have dirtied his hands had the news from the village not reached him that his father had died, but then Sklenár became horribly enraged. He hated everyone who stood around him, as it was the war that took his father, not his heart. His heart could have beaten for another 20 years. From then onwards, he aimed accurately, he didn’t care about tiredness anymore, as if he was reborn. Anger drove him, and within two days he shot more Nemec than the others altogether until then, his face puckered into a formidable grimace whenever he saw one, even though if he had pondered it over a bit he didn’t give a shit about them, and he didn’t care too much about his father’s death either, only the tension came out of him that way. He didn’t mind the hail of bullets, he just marched ahead, shot and shot, and when he couldn’t shoot anymore, he took out the little axe he got from his father. By the second afternoon, his coat and his face were covered in blood and blood clots were hanging from his hair. The others were trying to get out of his way, saying that the Sklenár had gone completely mad, asking where he thinks he is and that there is a limit to everything.

Then the Nemec surrendered, the gradual withdrawal turned into headless fleeing. The partisans didn’t try to break their bones, they just drank fruit brandy, except for Sklenár who chased the Nemec like a mad dog. He climbed up the hill, the sun was going down behind the hills, the beams of light still coming through the trees. One couldn’t tell the blood on the snow and the red sunlight apart. Everything was covered in blood, or it was as if everything was covered in sunlight. Sklenár stopped and still wheezing, he watched the red sea of light on the snow.

Then he heard the sound of cracking nearby. He turned and headed towards the direction of the sound. On a branch, hanging on a tree, a young, blonde Nemec was dangling. He had probably just pushed himself from the tree trunk. The noose of the thick rope tightened around his neck, his face was turning blue as he wiggled his legs. In the light of the setting sun, he looked like a straw man painted red and controlled from above by a puppeteer.

The rope has been under the Sklenárs’ bar for a good 40 years. It was an old belief, and earlier the more gullible people even paid the hangmen generously for one, because as the superstition had it, if one put a rope taken from a hanged man’s neck under the bar, the drinks would sell better. Vlado didn’t even know about it, only a few of the villagers suspected it, but even they only knew the story as far as when Sklenár cut the Nemec wriggling on the rope down in the last second.

With his last breath, the old Sklenár told Vlado the whole story, that the young Nemec must have regretted his deed right at the moment of pushing himself from the tree, and he looked pleadingly in the direction of Sklenár in vain. He just stood silently in the bloody sea of snow and waited until the Nemec’s body gave way and ceased moving. Only the glassy stare remained pleadingly fixed on Sklenár, the lines had smoothened on the young soldier’s face. For minutes, Sklenár looked into the dead eyes unmoved, then climbed up the tree and with his axe, he cut the rope that had been twisted around the tree.

“You owe us a lot and unfortunately, you have to pay for it,” he said, while he turned the body on its back, untangled the rope from the soldier’s neck, neatly rolled it up, slipped the precious treasure into his bag and left the Nemec lying on the floor behind him.

In his embarrassment, Vlado didn’t know what to say, he looked alternately at the old Škoda sanitka’s floor and the worn-out stitching of his faux leather botasky. He would have said something like that it happens sometimes, but he felt that it wouldn’t have sounded appropriate. Instead, he waited until the old man became silent and the sanitka, which was heading towards the town clinic, turned its siren off.

[1] Ubiquitous Czechoslovakian mineral water brand

[2] Make of Škoda typically used for Czechoslovakian ambulances

[3] German/Germans

[4] Czechoslovakian brand of trainers

[5] ushanka hat

[6] cemetery street

[7] Nova was a grape variety widely planted in Czechoslovakia which was later banned due its detrimental effects of the health of those who consumed it. It was believed to cause nerve damage and brain cell damage, blindness and hereditary. On the other hand, it was a robust and high-yielding variety that produced large quantities of wine. Nova is also the name of the collection of short stories of which this story is one.

[8] penny

Ajánlott bejegyzések:

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.